Ruins have long held my fascination.

Having knocked around a bit in Rome in 1984 as the Rome Daily America was in steep decline, I developed a more mature appreciation of the Eternal City’s dominance in this mystical arena. Was it any surprise that I should migrate over to the most desperate corners of failed enterprise when I settled in San Francisco?

During that era, one of our most rapidly decaying regions was its waterfront.

The Port of Oakland across the bay had captured most of the commercial cargo business, with cruise and passenger vessels opting to come here not at all. What remained resilient, and resilient still, is the ferry system.

I soon discovered that the best way to view a bayside ruin was by this elegant transport mode. Alcatraz and Treasure Island were on every “misery” tourist’s bucket list. But just as depressing were the abandoned warehouses and terminals along the ferry itinerary. Ghost industries haunted by distant memories of thriving commerce underway in the 1950s.

A major turnaround occurred during the 90’s, just after the storied “Loma Prieta Earthquake.”

With the Bay Bridge closed for several days, commuters were demanding that our existing ferry fleet be enlarged. Indeed, a

renewed vision of how the ports here could rebuild themselves took hold, capturing significant investment revenue from high-tech firms and venture capitalists.

Today, San Francisco has fully restored its past maritime glory, although mostly through the reliance on tourism. We also hosted the most dramatic “America’s Cup” in recent history with the Oracle Team coming back from almost insurmountable odds.

But what of the ruins?

The newly-vacated high rises are a consequence of the “work at home” movement taking hold here during the COVID 19 pandemic. Unfortunately, these heroic structures have yet to rust and crumble the way ancient buildings did centuries ago.

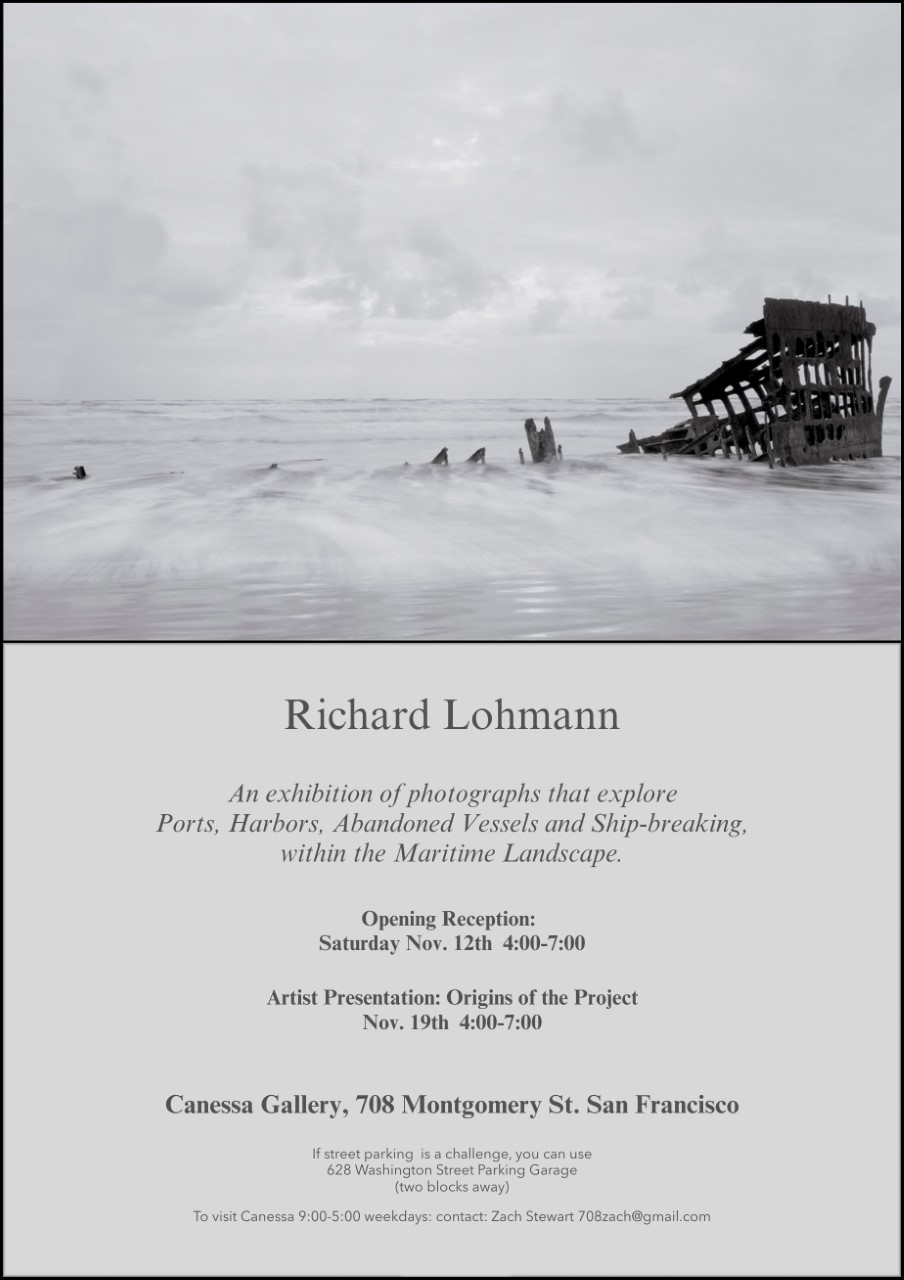

A recent exhibit of black-and-white photographs done by Richard Lohmann at The Canessa Gallery in San Francisco’s Italian neighborhood of North Beach speak to the lost romance of ferry travel on the Bay. As a recreational sailor, Lohmann discovered abandoned vessels and the detritus of disasters at sea and near the shore, some leaking toxic chemicals, an environmental disaster he helped to mitigate. The wrecks and the relics prompted him to conduct research about the history of ships such as the S.S. Garden City, a ferry that made hundreds of journeys, beginning in the late 19th century and that carried thousands of travelers from the East Bay into San Francisco, until it was abandoned in the 1970s.

Just up the street from the Gallery is the iconic City Lights bookstore, founded by the Italian-American poet, Lawrence Ferlinghetti in 1953. This old ruin is now celebrating its 70th anniversary, with readers being reminded that it too, has ferry roots.

After serving with distinction in the U.S. Navy during the Second World War, Ferlinghetti rode a train to Oakland before catching a ferry to San Francisco’s embarcadero station. In an interview I conducted for Publisher’s Weekly, he recalls that he thought he had reached Atlantis from the sea.”

City Lights also entered the publishing racket early, launching its iconic “Pocket Poets Series,” and thereby gaining infamy with Allen Ginsberg’s notorious “Howl.”

With this bookstore-publisher combination, says Ferlinghetti, “the public were being invited, in person and in books, to participate in that great conversation between authors of all ages…ancient and modern.”

A tribute to ruins, if there ever was one.

Romans may find our provincial ferry system rather quaint compared to the operations at Port of Civitavecchia, where passengers embark on far flung voyages and romantic adventures abroad. But we locals savor this exotic mode of transport above all others. For while we pass by, through and under various reminders of bygone glory, a promise of sustainable transit keeps us on a faithful course into the sublime.

About The American/InItalia:

The American is a pro bono independent general interest online magazine complied in Rome, Italy and edited by journalist Christopher P. Winner, who founded the publication in March 2004. It publishes more than 20 columnists on a regular basis.The American is not an incorporated company and does not accept advertising or issue invoices. All submissions are published on a pro bono basis. The American takes its name from the Rome Daily American newspaper (1945-1984). It is a non-partisan, general-interest monthly dedicated to giving Italy’s English-speaking residents and foreign readers insight into Italian national culture, politics and lifestyle while also offering essays and opinion pieces unconnected to Italy. The magazine is not connected to or subsidized by any U.S. institution or government agency. All contributions are voluntary.